Hero image generated by ChatGPT

This is a personal blog and all content herein is my own opinion and not that of my employer.

Enjoying the content? If you value the time, effort, and resources invested in creating it, please consider supporting me on Ko-fi.

Background

Microsoft Edge introduced Drop as part of its sidebar ecosystem as a quick, frictionless way to share notes and files between signed-in devices using OneDrive sync.

On the surface, it’s a useful feature: lightweight personal transfer without the clutter of email or Teams.

But convenience often conceals complexity, and this one concealed something more subtle

.

While testing an unrelated behaviour in Edge’s sidebar, I noticed something odd.

Messages sent through Drop never appeared in DevTools’ Network tab.

There were no visible POST requests, no telemetry endpoints, nothing surfacing in packet captures.

Yet, somehow, the files and text always appeared on the other device.

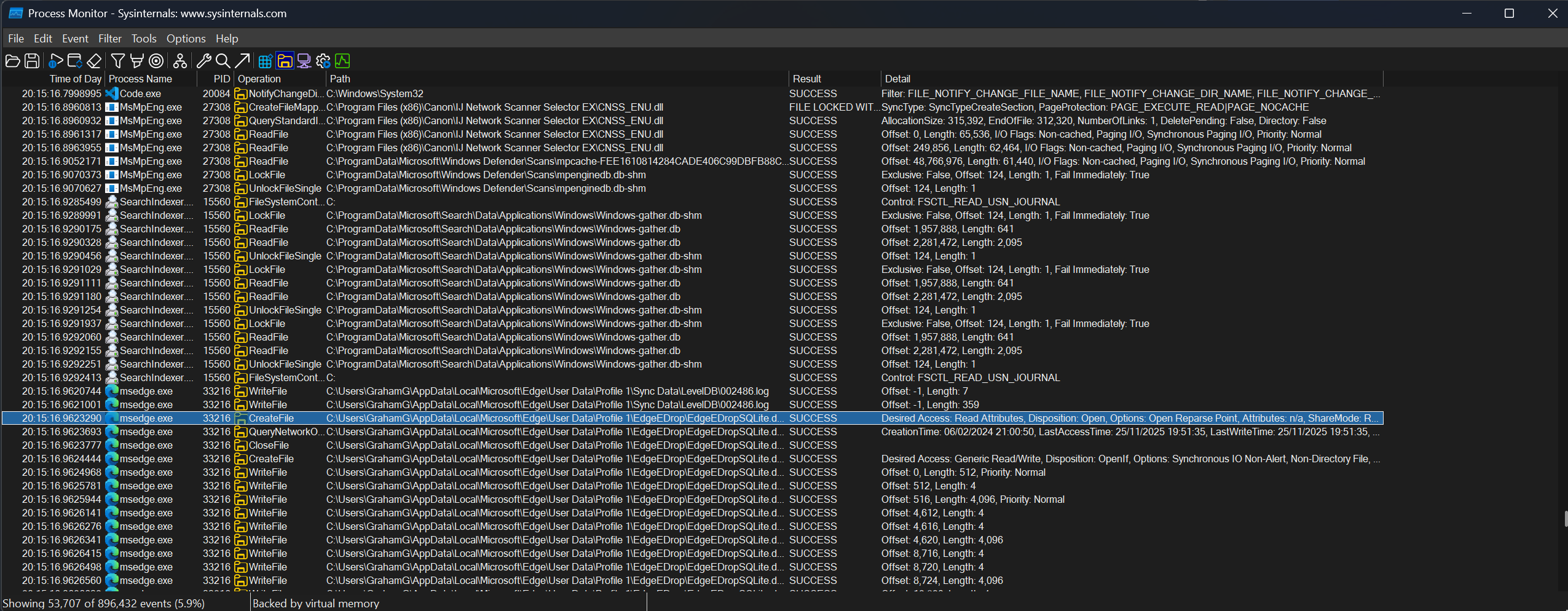

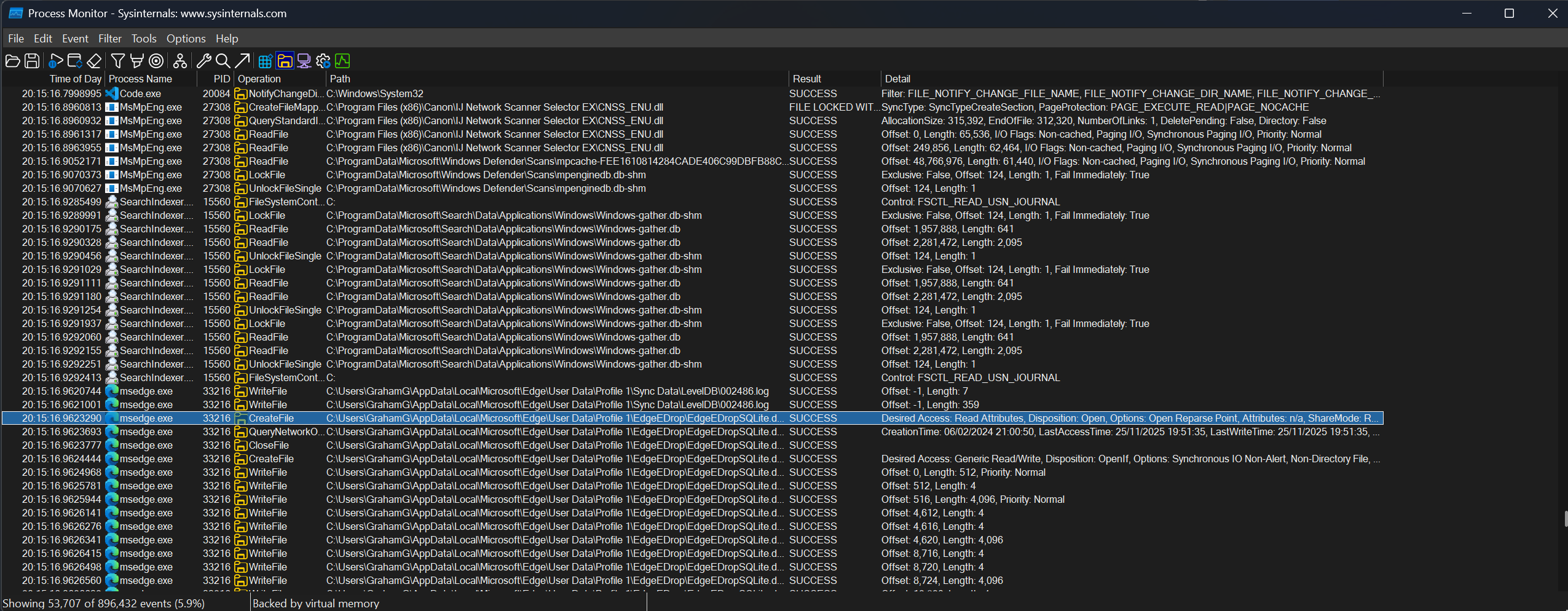

That inconsistency led to a deeper dive with Sysinternals’ Process Monitor and eventually to a local SQLite database quietly written inside the user profile directory .

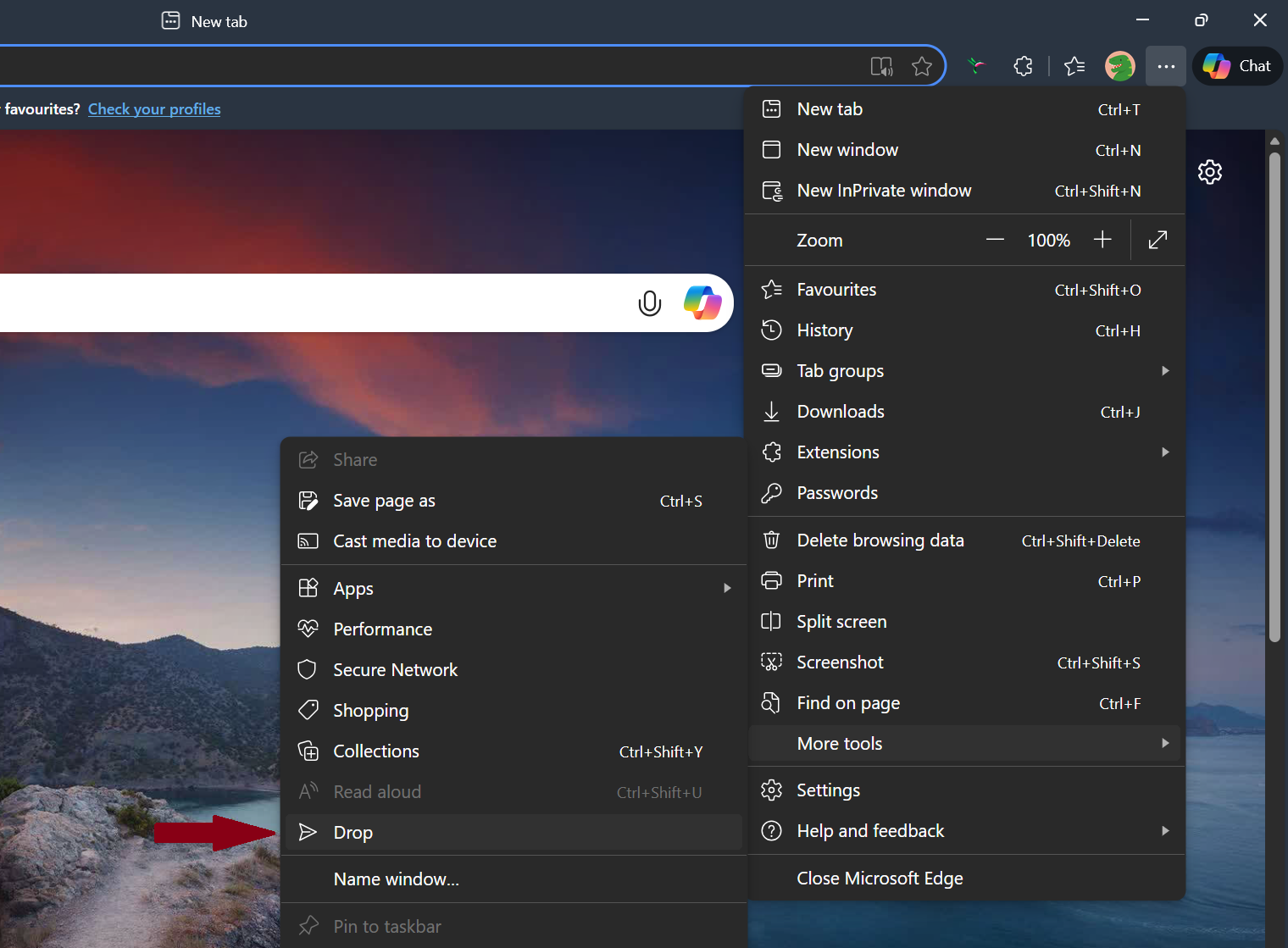

You can open Edge Drop by navigating to ... > More Tools > Drop

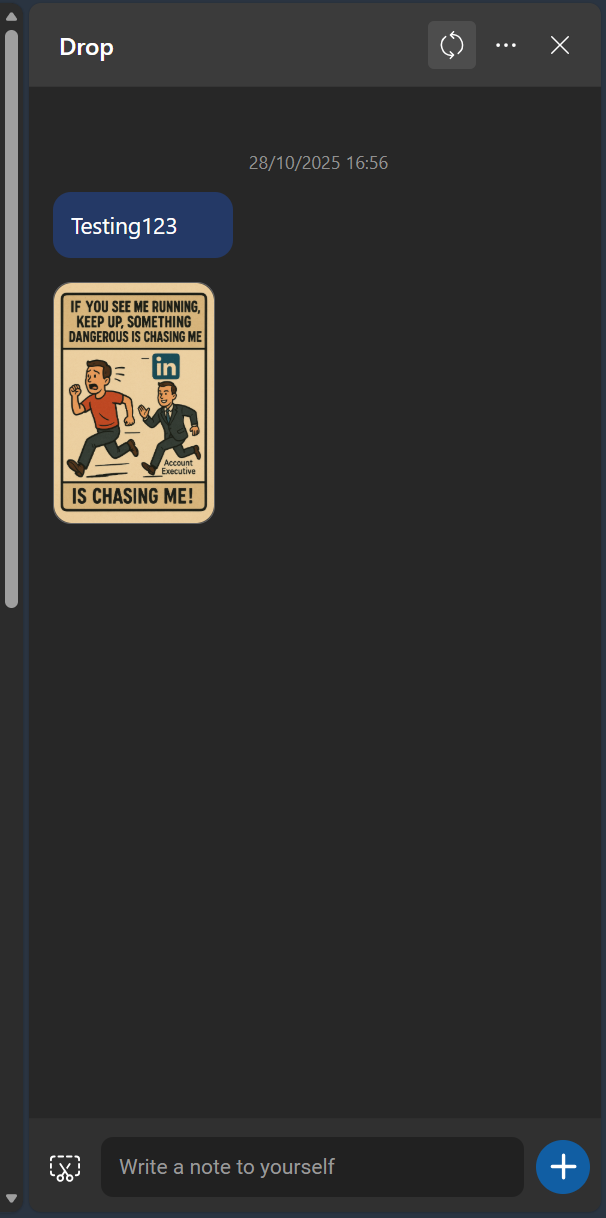

You then see the Drop sidebar/chat:

Discovery

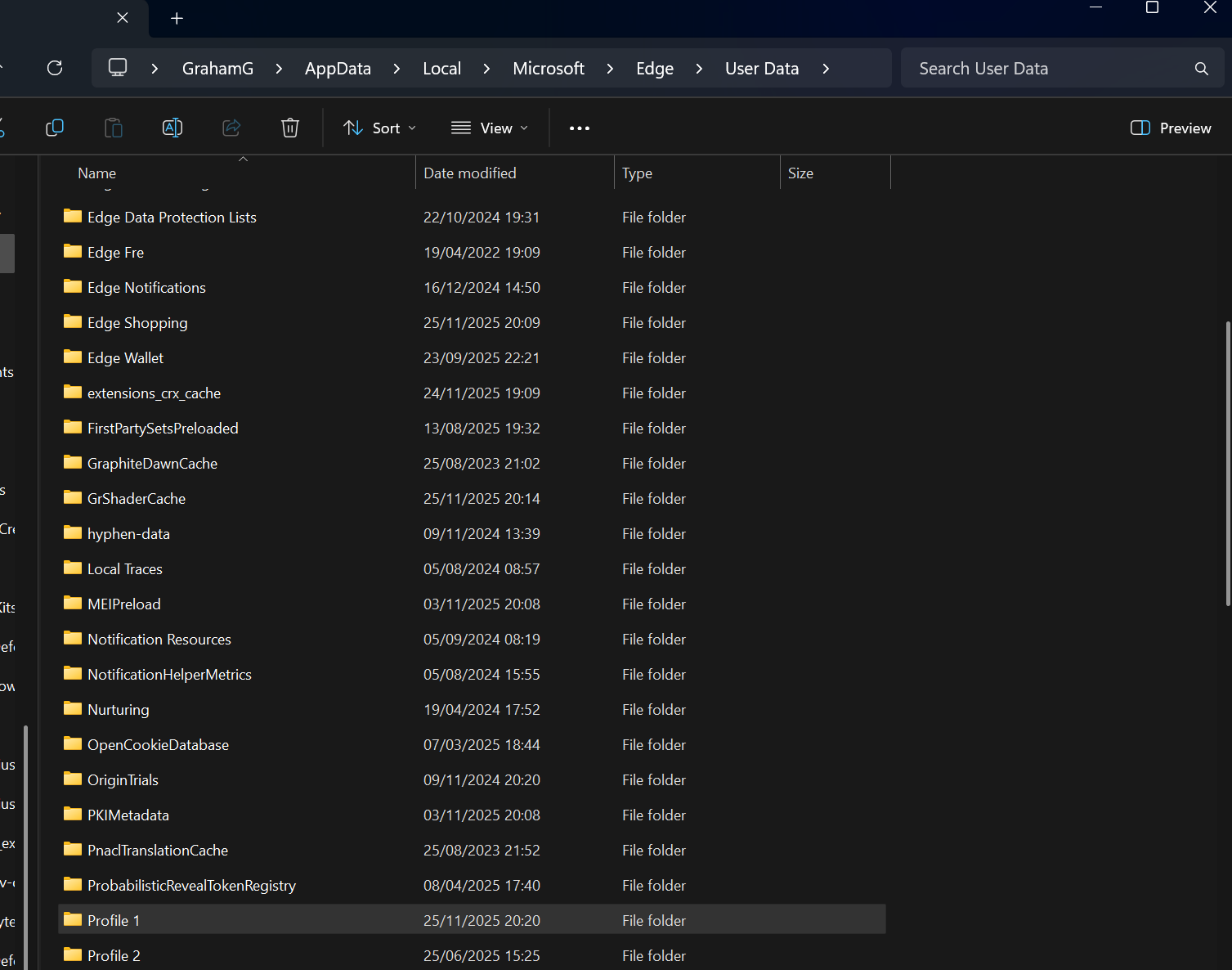

Within %LOCALAPPDATA%\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\{profile name}\EdgeEDrop\ sits a file named EdgeEDropSQLite.db.

(Profile name may be Default, Profile 1, Profile 2 etc)

When opened, it tells a simple but concerning story:

- Table

messagesstores every piece of text a user sends through Drop – in plaintext. - Table

attachmentsholds references to the uploaded file(s) stored in OneDrive underMicrosoft Edge Drop Files. - WAL and SHM files, if they exist, retain deleted content well beyond user interaction.

The data is fully readable by any process with access to the profile directory. No DPAPI encryption, no per-profile keying, no obfuscation

.

And because the sync occurs asynchronously through Edge’s browser-sync channel, no direct network transaction is visible when the data are written.

From a security perspective, that means:

- Security tools see nothing with the exception of local file writes, not exfiltration, within the user profile directory (low fidelity signal from a detection perspective).

- Backup agents and snapshots preserve the plaintext cache indefinitely.

- Multiple browser profiles replicate the issue independently for every signed-in user context.

You can try to open the .db file and you can sort of read it even though it’s a binary file:

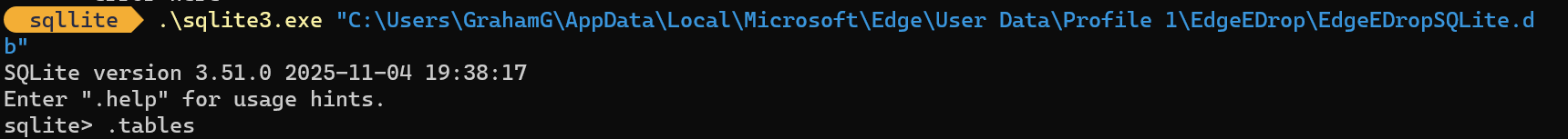

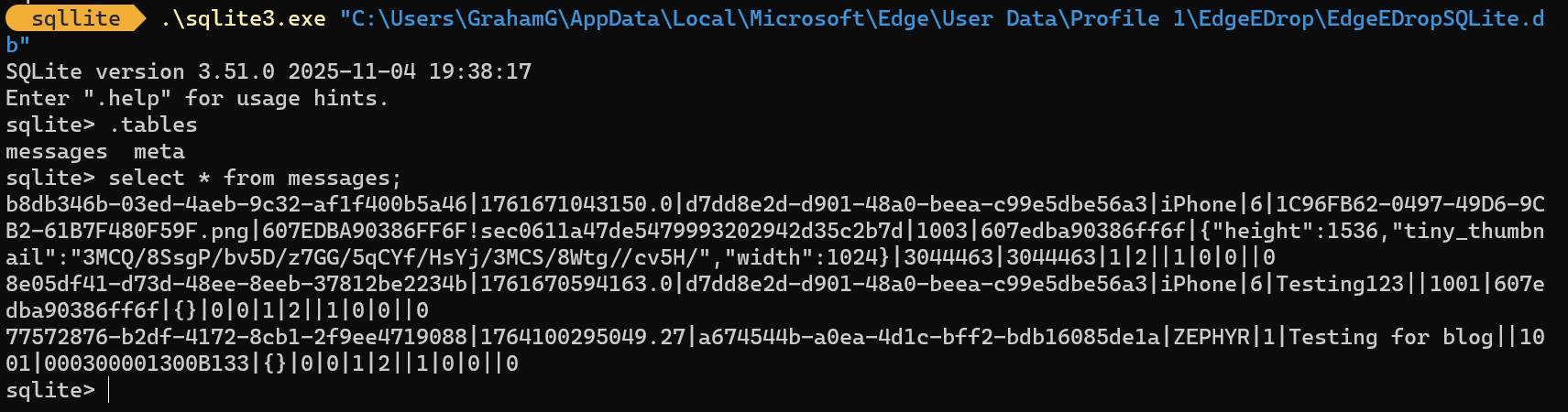

You can also download the sqllite client and use it to interrogate the database:

Invoke-WebRequest https://sqlite.org/2025/sqlite-tools-win-x64-3510000.zip -OutFile sqllite.zip

Expand-Archive .\sqllite.zip

cd .\sqllite\

\sqlite3.exe "C:\Users\GrahamG\AppData\Local\Microsoft\Edge\User Data\Profile 1\EdgeEDrop\EdgeEDropSQLite.db"

SQL queries:

.tables

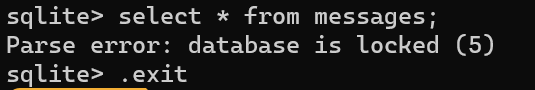

select * from messages;

If Edge is still running (even if you’ve closed it, you will have to kill all edge processes in Task Manager), you will get database locked errors:

Once all Edge processes are killed:

Impact

This is not an exploit in the conventional sense - it doesn’t cross a security boundary or grant new privileges.

It’s a data-handling flaw: a design that assumes personal use and privacy, but behaves identically in enterprise contexts where those assumptions fail

.

Local Persistence

Any process running as the user (including malware, scripts, or backup services) can read the SQLite file directly

.

In managed environments, shared admin credentials or endpoint management tools may also have access to those paths.

Backup and Replication

Enterprise backups, Volume Shadow Copy Service (VSS), and consumer backup services capture the plaintext data by default.

A single note containing a credential or token becomes a permanent artefact across multiple systems

.

Policy Control

The edge policy setting EdgeEDropEnabled controls Drop globally.

However, unless explicitly disabled, it is enabled by default on Windows 11 Enterprise installations.

The setting is also able to be set via Group Policy: https://www.syxsense.com/syxsense-securityarticles/cis_benchmarks_(ms_edge)/syx-1038-13686.html

Not all organisations import the latest Administratative (ADMX) templates, meaning the feature activates silently across managed fleets.

The CIS Level 2 benchmark setting for this states the following:

Description

Drop is a space to instantly share files and content across mobile and desktop devices.

This policy setting enables or disables this feature. Enabling this feature can pose a security risk as there’s a possibility of sensitive data being mistakenly or intentionally sent to unauthorized devices or third parties. Such an act could inadvertently expose confidential information, leading to potential security breaches and data leaks.

Impact

Sensitive data, such as personal information, proprietary company information, or financial details, could be inadvertently sent to unintended recipients.

Once sent, the data could fall into the wrong hands, leading to unauthorized access and potential misuse.

Amplified by Conditional Access

Modern identity strategies encourage users to sign into browsers with Entra ID (formerly Azure AD) to satisfy Device-Based Conditional Access.

Each compliant device therefore hosts a fully authenticated browser profile and with it, a local plaintext cache of Drop data.

The stronger the identity enforcement, the wider the propagation of this unencrypted store

.

Responsible Disclosure

A full technical report was submitted to the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC), including:

- Reproduction steps,

- Evidence of plaintext storage,

- Procmon traces of file writes and background sync,

- Screenshots of the SQLite tables, and

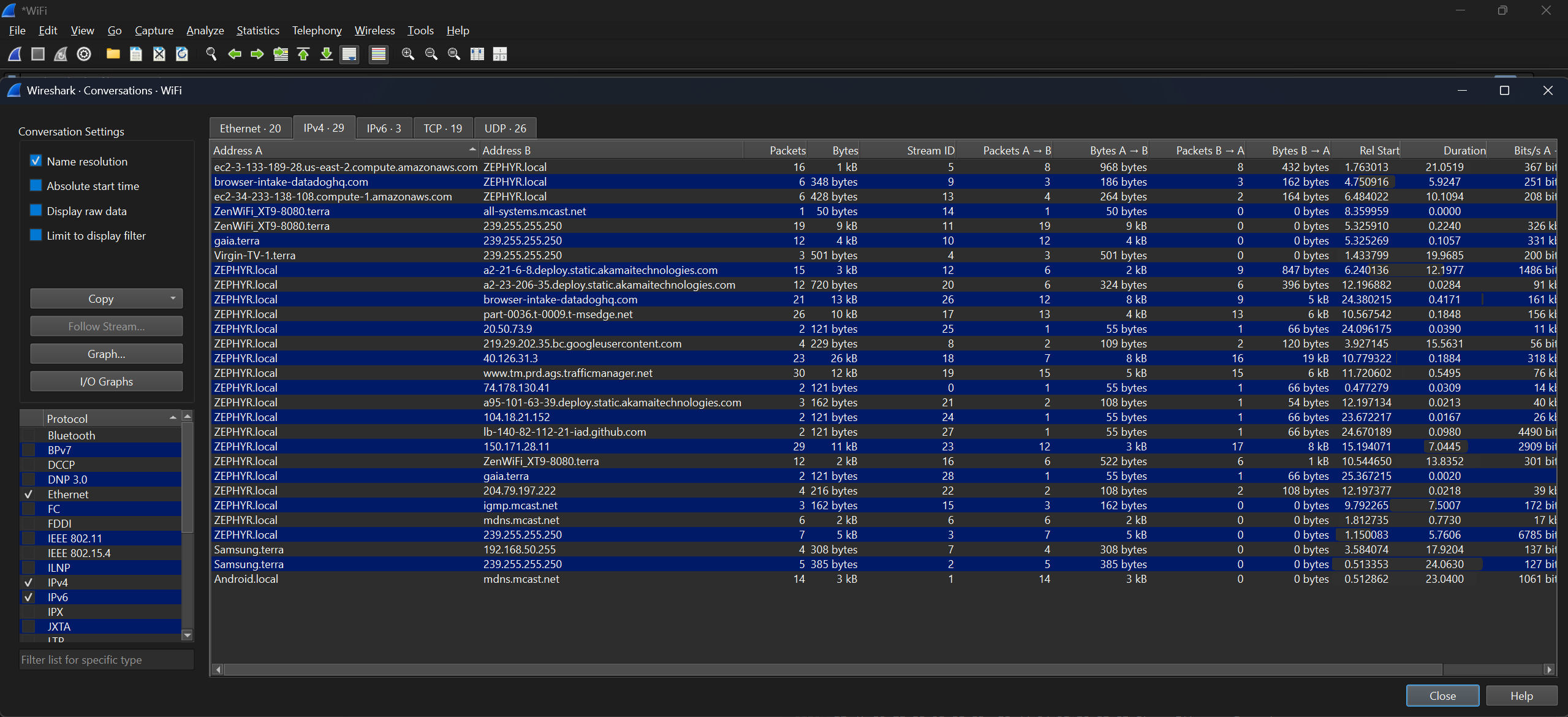

- Network capture summaries confirming the absence of visible upload traffic.

Timeline

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| Early October 2025 | Discovery during local testing |

| Mid October 2025 | Full technical report submitted to MSRC |

| Late October 2025 | MSRC triage completed and response issued |

| Publication | Planned after official case closure and vendor review |

Microsoft’s Response

Thank you again for submitting this report to the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC).

After careful investigation, this case has been assessed as not a vulnerability and does not meet Microsoft’s bar for immediate servicing due to:

This scenario does not bypass a security boundary. If you already have code execution as the user or can read the file contents, you could simply attach to Edge and wait for the data to be decrypted.Based on this, it does not qualify as a vulnerability. MSRC prioritizes vulnerabilities that are assessed as Important or Critical severity.

Since this case was below the bar for immediate servicing, it is not eligible for bounty, and no CVE will be issued.

MSRC will not be tracking this issue further, and no additional updates will be provided.For more information on our security vulnerability servicing criteria please refer to the following resources:

- Online Services Vulnerability Researcher: https://www.microsoft.com/msrc/olsbugbar

- Windows Vulnerability Research: https://www.microsoft.com/msrc/windows-security-servicing-criteria

- AI Research: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/msrc/aibugbar

- Bounty information and current programs: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/msrc/bounty

- MSRC Researcher Resource Center: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/msrc-msrc-researcher-resource-center

Thank you for your submission. We appreciate your partnership to help secure our customers.

– Microsoft Security Response Center (MSRC)

It’s a polite and predictable answer: technically correct, procedurally consistent, and yet missing the risk from an enterprise perspective.

Why It Matters Anyway

By Microsoft’s servicing criteria, this is not a vulnerability because it doesn’t cross a “security boundary.”

From an architecture and data-protection standpoint, it’s still a serious oversight

.

The moment a user signs into Edge with corporate credentials, that local Drop cache becomes an enterprise data repository: unencrypted, unmonitored, and quietly replicating between devices via OneDrive.

It doesn’t matter whether the attacker is external or internal; the problem is that data believed to be transient is instead persistent.

That persistence is invisible to all the layers enterprises rely on because the sync traffic is embedded within a trusted browser process

.

Security tools detect file writes, but not the silent sync channel.

Edge Drop:

- works in Edge on multiple platforms (I tested Windows and iOS (on an iPhone))

- evades detection

- syncs asynchronously using non obvious urls

- If you delete the db file or reimage the OS - sign back in and all the history (text and files) is back in very short order.

The False Comfort of “By Design”

“By design” is technically accurate. It’s also the problem.

The issue isn’t the lack of a fix; it’s the lack of a boundary definition that considers how identity, sync, and persistence interact

.

A browser profile is no longer a personal container; in an enterprise world, it’s an extension of the corporate boundary

.

When that profile stores sensitive data unencrypted, the boundary moves silently inward and none of the surrounding controls know it’s shifted.

Lessons for Secure-by-Design

This is the sort of scenario that Secure-by-Design principles were meant to catch:

Assume enterprise presence.

Any consumer feature deployed at enterprise scale inherits enterprise risk.Encrypt local caches by default.

DPAPI or platform keychains exist for a reason. Their absence here is a choice, not an oversight.Expose administrative controls early.

If a feature can move data, admins should have explicit policy levers to disable, restrict, or audit it.Don’t conflate local access with low impact.

Data at rest on a managed device is subject to a completely different threat model than on a personal one.Visibility is a feature.

Silent background syncs may feel seamless to users but render enterprise monitoring useless. Transparency should be optional to disable, not impossible to achieve.

Broader Implications

This isn’t about Edge specifically; it’s about the broader industry trend of convenience-first.

Every major platform is chasing continuity; the frictionless movement of content between devices and identities

.

But in the process, we’re erasing the very seams that make data boundaries comprehensible.

When everything is trusted, nothing is visible.

And when nothing is visible, “by design” becomes a very convenient phrase indeed.

Closing Thoughts

Responsible disclosure is an odd ritual.

You gather evidence, write responsibly, report politely, and then watch as the machine hums to life, only to tell you that the machine is working exactly as intended.

Edge Drop isn’t malicious. It’s just another reminder that security boundaries are social constructs, not technical ones.

We draw them where they’re convenient, not where the risk actually lives.

Microsoft is right that this behaviour doesn’t cross a traditional security boundary.

But it does cross a trust boundary; and those are the ones that matter when data travels further than anyone realises

.

Because in the end, a single note dropped into the cloud isn’t the problem.

It’s the quiet certainty that hundreds of them already have been; syncing happily, silently, and perfectly by design.

A silent drip becomes a flood.